Negative Interest Rates: Coming Soon To A Bank Near You?

If you live in the United States, chances are you won’t be seeing negative interest rates at your local bank, at least for the foreseeable future. However, citizens in Europe and Japan face a real possibility of facing negative rates at their bank branches, as central banks in nine large countries have now set key rates below zero. Meanwhile, negative bond yields have become normal around the world. According to Bloomberg data, last week over $7 trillion of the world’s bonds had negative yields; this amounts to over 25% of global developed country bond debt! The U.S. bond markets are not immune; some treasury securities (Tbills) have offered negative yields in the past year. While economists continue to debate the efficacy and impact of negative rates, the move below “the lower bound” of zero is a new phenomenon.

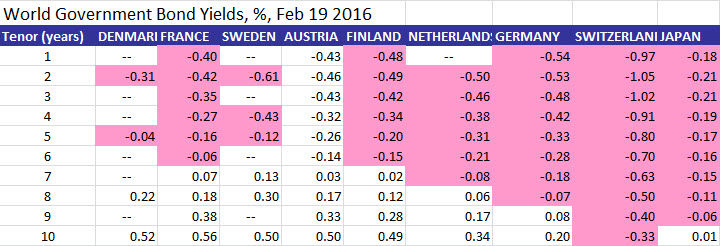

To most people, negative interest rates and negative yields sound illogical, if not impossible. Applied to the banking sector, negative rates mean that the depositor has to pay the bank to hold his/her cash. If deposit rates were -1%, for example, for every $1000 deposited in a bank account, the holder would have around $990 at the end of the year. Similarly, when a bond offers a negative yield, the buyer of the bond does not get the total invested amount returned to him/her at maturity. In Germany, a one-year government bond currently yields roughly -0.5%; buy this bond and you get less euros at maturity than what you put in. On face value, these negative rates do not sound like a good deal, yet a multitude of investors pile into negative yield debt across many countries such as Germany, Denmark, and Japan. Banks in these nine countries have to pay central banks to hold their cash balances.

Why this apparent crazy behavior? Subzero rates attract investors under a few circumstances. First, when investors are risk averse and scared of losing money in risky assets, they flock to the “riskless” investments such as cash and government bonds. They are willing to accept low / near zero returns because low is preferred to an actual loss. At small negative interest rates, these risk-averse people will cling to a low, certain loss rather than a potentially higher uncertain loss. It may take deeply negative interest rates to make them pull their cash out of banks or government bonds.

Second, in a deflationary world, negative deposit rates or bond yields can still yield positive real returns. For example, if inflation is -2% and deposit rates are -1%, the investor still makes a “real” return of 1%. With this level of deflation, prices of goods fall through time (they become cheaper by 2% a year in this example) yet the investor only loses 1% on his bank deposit. This means he still has a 1% increase in his real purchasing power even with negative rates.

Central banks such as the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan have brought interest rates negative as part of their plan to stimulate growth. By penalizing banks for keeping cash on deposit, they hope to encourage them to lend more to customers and thereby encourage investments and expand the economy. In order for the plan to be effective, people and companies have to want to take out the additional loans. It’s too early to tell if it is working.

One fear that experts have regarding negative deposit rates is that customers could try to pull their cash out of “costly” banks and store it under the “free” mattress. While possible for small accounts, wealthier clients and corporate customers would need a very large mattress! So far we haven’t observed a significant withdrawal from bank accounts within the nine negative rate countries, as banks have not passed their negative rates onto individual customers. However, some large corporate clients are getting charged for big balances; as such negative rates will continue to induce these companies to make new investments, or merely use cash to buy back outstanding stock or debt, or even buy other companies. Overall, most analysts agree that negative rates will hurt the banks’ profits before it hurts the banks’ customers.

Still the concept of subzero rates is looming in U.S. financial circles. Last week the Chairwoman of the Federal Reserve Janet Yellen told Congress that she was open to bringing U.S. rates negative if the economy warranted it. Technocrats in the U.S. and a host of other countries are readying regulations and infrastructure in order to prepare for the possibility. However, while the stock and commodities markets have been volatile and painful of late, the U.S. economy is just not that bad off. The underlying labor market has shown continued strength and consumption has been resilient. Consequently, the U.S. is far from needing another big round of monetary policy easing, especially in the form of negative interest rates.

Hopefully our economy won’t need a drastic move to negative rates in the coming years, as there is not much consensus among experts that this kind of monetary policy does more help than harm. In the years since 2008, markets have generally applauded aggressive moves in easing monetary policy as powerful stimulus to kick-start economies. However, in the weeks since Japan went to negative rates, markets are expressing the view that monetary policy doesn’t seem to pack the punch it used to. It is time for the fiscal policymakers to get some tough reforms done.